Cambodia's underwater de-miners

A former soldier tries to atone for the sins of his past, while another just wants to learn to swim. They're both recruits hoping to join what would be the country's first team of underwater de-miners. A radio feature for PRI's The World.

Preah Sihanouk, Cambodia

By a glimmering pool on top of a new condo tower in Phnom Penh, three dozen men are crouched doing push-ups. They're in training, as part of a US-government funded project with Cambodia's de-mining agency.

They want to become members of the country's first team specializing in recovering underwater UXO, or unexploded ordnance.

But first, they have to prove they can swim.

In Cambodia, long-buried landmines and other explosives left over from decades of war still kill or injure more than a 100 people each year. For years, Cambodian deminers have been working to reduce the threat, clearing tens of thousands of acres of contaminated land. Now, Cambodia wants to do this underwater.

“When I clear the landmines, I’m pretty scared. But I feel so guilty. I feel like I have to take the landmines out.”

Like most of the recruits here, Chan Song never had a swimming lesson, but that didn't stop him from signing up.

"I've swum before in the river," says Song, a deminer with the Cambodian Mine Action Center, the government demining agency. "Nobody taught us how to swim. We taught each other."

At 45, Chan Song is one of the oldest recruits. He's already used to removing deadly explosives from the ground. But for him, this work is personal. He laid landmines himself, when he was a soldier.

"When I clear the landmines, I'm pretty scared. But I feel so guilty. I feel like I have to take the landmines out. If I don't do it, maybe they could hurt my own relatives."

Remnants of war

In the early 1970s, the US-backed government of the day was fighting a losing battle against Khmer Rouge rebels. To resupply troops on the frontline, authorities sent ships with ammunition up the Mekong River.

"So these boats would be carrying their cargo of ordnance to resupply some forward fighting force, and they'd be fired upon by the enemy and sunk," says Allen Tan of the US-based Golden West Humanitarian Foundation, a UXO removal research group that is leading the dive training.

"So there they sit at the bottom of the river. Well, people start finding this stuff now."

Tan says there are likely thousands of tons of sunken munitions in Cambodian waterways. And they've become prime targets for scrap sellers, who dig them up for the metal.

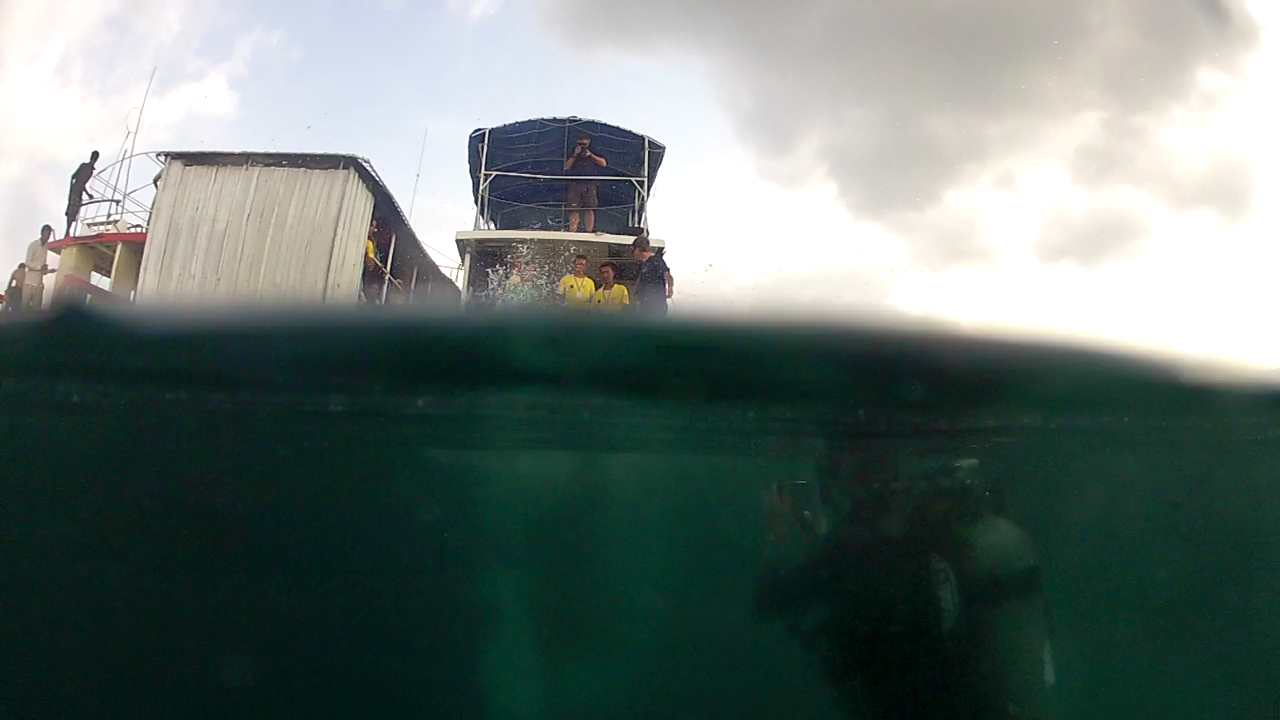

Two weeks later, the recruits are on a small dive boat in the ocean, about 12 miles off Cambodia's coast. Fewer than half have made it this far.

Robert Rice, an instructor here, looks on as two recruits jump into the bright blue water. The first lesson: how to navigate as a team, using a compass. But there's some confusion below, as a trainer following the pair underwater reports back.

"Both almost cracked the surface then went back down," the trainer says. "Then there was a bit of pushing and shoving about where they were going to go. There was no real discussion. So they're not really talking to each other."

First steps

It's a steep learning curve for these recruits. Underwater munitions recovery is an inherently risky operation. The Mekong River is lined with silt and mud, which could mean almost pitch-black diving conditions in a fast-flowing river.

Rice knows the challenges the recruits will face — he's a former US Navy EOD diver (explosive ordnance disposal).

"Everything has to be able to be done by touch, including awareness of where they are in the water column, how deep they are, awareness of where they're buddy is. In the complete blackness, that will be a big challenge. And the fact that the water's moving is another big challenge," Rice says.

"Then you've got to go find the ordnance, and blind, you have to decide, is it safe to move? Is it ordnance? What sort of ordnance it is?"

Later in the day, the recruits take a short break. Chan Song, the deminer who felt a personal obligation to remove landmines, didn't make the cut. But another former soldier, Tri Khun, did and he says he's getting the hang of diving.

"At first, it seemed completely more dangerous working in the water, compared with demining on land. But it's getting better since training started. I think it will be easier than on land."

But this is just the beginning. Months of training still lie ahead. If all goes well, and additional US funding comes through, officials here hope to have a qualified team of underwater UXO specialists within a couple of years.