West Kalimantan, Indonesia

That’s a problem for many indigenous Dayak communities, who live amid massive palm oil plantations and logging companies on their traditional lands.

But some people are using basic mobile phones to fill this media void. They’re texting the news, and they say it's making a difference in their lives.

The citizens of Indonesia are among the world’s most avid users of the Internet and social media. But not everyone is so well-connected in the sprawling archipelago nation.

In remote corners of West Kalimantan, the closest village may be hours, even days away and getting the news in — or out — can be difficult.

Adrianus Adam Tekot lives in a village outside Pontianak, West Kalimantan's capital. He's one of several people who have been trained to send news from his village by SMS, or text message.

“At first, there were no journalists who willingly wanted to come to this village,” he says. “But by being a citizen journalist, I can be sure that I convey the facts about the environmental issues from the palm oil companies in this area.”

“There were no journalists who willingly wanted to come to this village.”

The road to Adrianus' village is a bumpy dirt path that cuts through miles of palm oil plantations. Officially, it's the national highway, but the road even a few miles outside Pontianak is jolting at the best of times, and virtually impassable during the rainy season’s wettest days.

Text messages from Adrianus and his colleagues have spurred sustained local media coverage on issues that have long antagonized the communities: pollution from plantations, key bridges left in disrepair, government offices that rarely open. The conditions of the main road — the responsibility of the palm oil company to maintain, he says — is a constant source of news.

“There is a gap between the traditions of the people and the modernity coming from outside.”

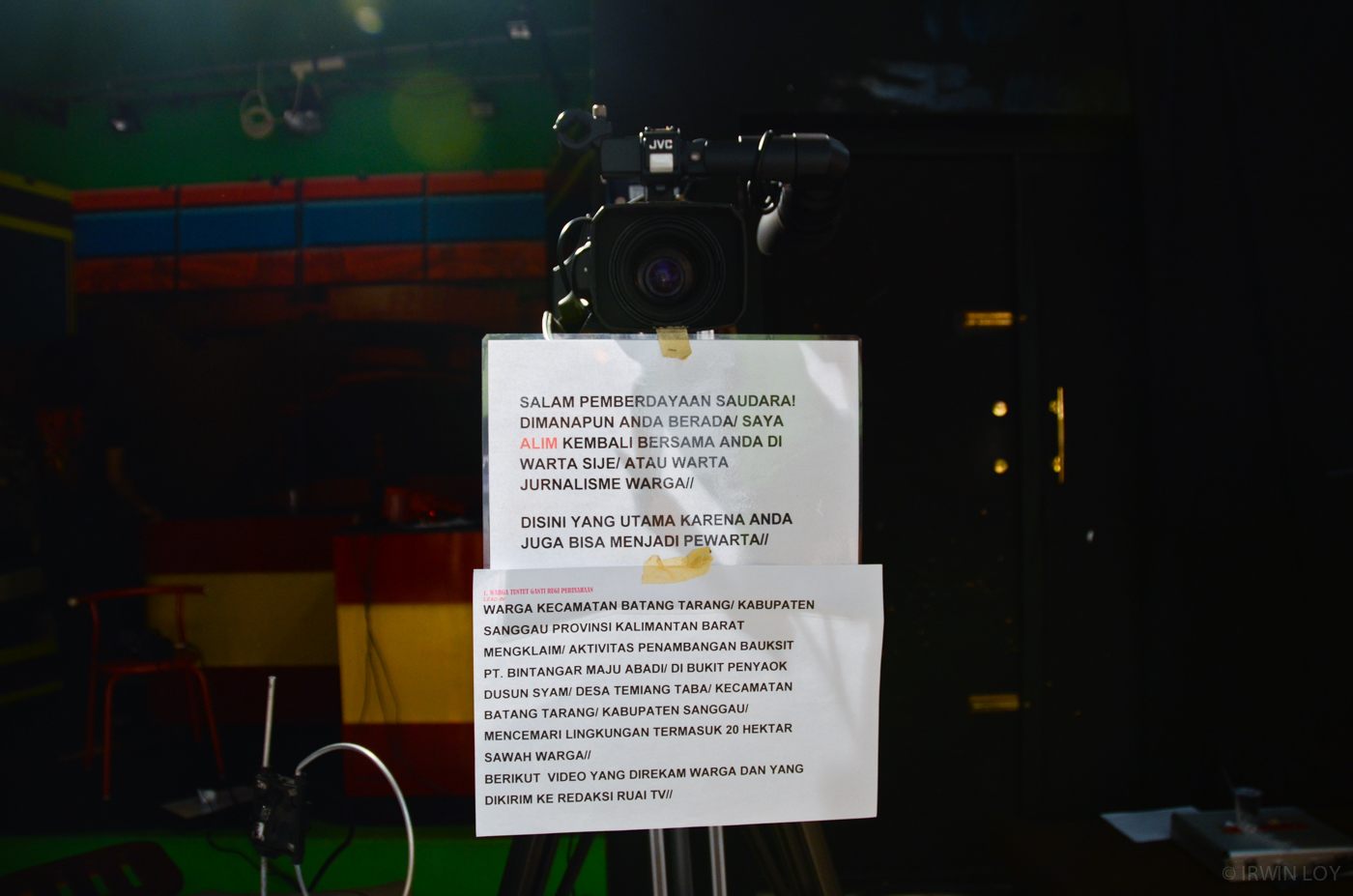

Citizen journalists like Adrianus send their news to RuaiTV, a television station in Pontianak focused on indigenous Dayak communities. A team of journalists receive the text updates and follow up on promising leads, attempting to confirm facts. Verified news tips are distributed, also via SMS, to a list of subscribers that includes local residents and government officials.

Jakarta-based journalist Harry Surjadi founded the RuaiSMS program because of what he sees as a dearth in coverage of key environmental issues in the Indonesian media.

“If there are hundreds of land conflicts, then it should be big news in the newspaper, but it’s not," he says.

He still keeps the first SMS sent by a citizen journalist — Adrianus — on his phone.

“One hundred indigenous people have occupied 21 hectares of an oil palm plantation,” the message reads. “The occupation started at 8 in the morning and they say they will stay until the company agrees to negotiate.”

Stefanus Masiun is the director and co-founder of RuaiTV. A Dayak himself, he says indigenous communities have traditionally been marginalized.

“Indigenous peoples in West Kalimantan mostly don’t have access to media. They don’t have access to services,” he says.

Alim, who uses one name, is a journalist and host of RuaiTV's evening news show, which features news and updates sent in from citizen journalists like Adrianus.

He believes his work helps to preserve his cultural traditions amid rapid development.

"Whenever there is anything happening in the community, I can get the news directly and I will put it out in the media," he says.